|

[June 23rd 2003]

6 questions about digital art

Interview with Andreas Broegger

Andreas Broegger is

a significant source of knowledge on digital art forms in general,

and net art in particular. Thomas Petersen has asked Andreas

six questions about digital art, which has resulted in an extended

journey through part of the topics and problems related to the digital

art forms of the present. The interview is stuffed with links to

new and old works and can be used as a platform for doing some serious

net art surfing. The interview was translated by Sofie Paisley.

On a daily basis Andreas is a PhD. and teaches classes

on digital art at the Department of Comparative Literature at the

University of Copenhagen. He is visual arts editor of Hvedekorn

and contributor and former co-editor of afsnitp.dk (among other

things he was curator on the net art project ON OFF 2000-2001).

Since 1995, he has been an art critic for Information, Weekendavisen

and Politken, and has published articles in amons others: Kritik,

Øjeblikket, Periskop, SIKSI, Flash Art, rhizome.org, noemalab.com.

You can catch up with Andreas at this email address: broegger@hum.ku.dk.

See also Andreas

Broegger's introduction to software art.

See

also Andreas Broegger's interview with Mark Napier: 'The Aesthetics

of Programming'.

See

also Andreas Broegger's excellent survey text: 'Net art, web art,

online art, net.art'.

We could begin by establishing a focal point in the multitudes

of net art strategies - can you mention a recent work which has

had special meaning for you, and which sets out an interesting course

for net art?

As a 'focal point' we could take a work, which kopenhagen.dk's readers

might have experienced, namely Victor Vina's work Flux

exhibited at Electrohype in Malmoe in October 2002. This work combines

several different features which I find characteristic of net based

art at the present, in relation to the earlier net art all the way

back from 1994 and most of the end of the decade.

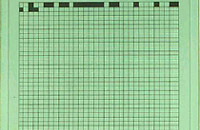

Victor Vina: Flux from Electrohype 2002. The images

were found at www.dosislas.org/flux and www.electrohype.org.

Described briefly, the project attempts to visualise and make palpable

the network's information flow in the shape of small, perfectly

done metal boxes with green displays, on which an eye can be kept

on what people around the world are searching for at the moment.

Search words and data are collected from a well-known search engine.

Vina discretely stated which search engine, but he does not want

this information made public, as it is illegal to hack into it,

so why not respect that. By touching the metal boxes you can then

further the searches appearing on the individual displays. Flux

contains traits characteristic of a lot of net art in recent years.

Flux looks rather good, data is encapsulated in sort of

miniature-minimalist metal boxes, there is an excellent idea behind

it, i.e. checking the pulse of our use of the internet by tapping

into a search engine, this takes place through a physical interface

designed by the artist, and finally there is a typical pointing

to something secret and border breaking (the illegal) as part of

the role of net art.

On the negative side, I see it as symptomatic that Flux

does not want to do very much with the data gathered and displayed.

It is a bit like WAP-ing from your mobile phone combined with monitoring

other people's searches on MetaSpy.

As far as the visual expression is concerned, Flux can be

compared to Listening

Post by Mark Hansen and Ben Rubin who, however, make more

of their data by incorporating the exhibition space. Contents wise,

I will place it within the context of works such as Common

Reference Point by Mark Daggett and Jonah Brucker-Cohen,

which (according to plans) similarly to Flux gathers and

visualises the net's flow of data, but simultaneously also deals

with the content plane of these data, first and foremost in a symbolic

connection (as a changeable virtual memorial of the 9/11 acts of

terror) but also as an analytical tool offering something else and

more than Flux's rather abstract picture of a flow.

Images from www.metaspy.com and Mark Daggett

and Jonah Brucker-Cohen's Common Reference Point.

It is thus possible to create links to texts regarding 9/11 found

by the project's search engine, and Common Reference Point

can tell us something about for example searches and locality, geographical

concentration, and the like. For comparison, Flux is not

particularly functional as "search engine". Even though

simplicity is a virtue especially in relation to the WWW, I feel

that there could have been one more level of reflection in Flux.

You might think that this is symptomatic of a lot of net art in

comparison to other visual art, but I do think that net art or any

art utilising telecommunication technology has and will have a lot

to offer in the present and in the years to come.

You write about the many genres of net art that have emerged.

I would like us to touch upon a couple of chosen 'types' of net

art and the different possibilities inherent in these.

Instead of talking about different types of net art it might be

better to talk about different 'dimensions' in the individual net

art projects - such as tactical media, data visualisation, design,

telerobotics, physical net interfaces, etc., as the majority of

works have by now become a mix of several of these things, as opposed

to being pure entities. The projects I mention here are all examples

of this. Some mourn that net art is already 'over', mainly because

the net looks a bit different today, is regulated and used in other

ways and because the art institutions and others empowered to give

grants, are beginning to influence this form of art in a particular

direction. In one way this is true when you compare it with the

early phase within net art. I am, however, not sure that going beyond

this phase is purely bad - it is also a new situation, a new challenge.

In general, I think that one of the most important things currently

happening to net art is that its borders are substantially widening.

Net art's early eagerness towards defining itself (being e.g. strictly

net specific) is giving way to a looser defined practice which can

include elements of a physical installation, and where the whole

concept of the net is expanded as e.g. visually based mobile telephony

becomes more widespread, and wireless internet connections in the

public space becomes a reality. I think this will change the perception

of what making art 'on the net' means - i.e. a convergence of WWW,

GSM, BPS, SMS, AM/FM, TV, and what else you might think of.

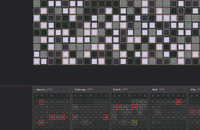

Images from Chaos Computer Club: Blinkenlights

and 0100101110101101.org's VOPOS.

As an example see projects such as Chaos Computer Club's BlinkenLights

and Jonah Brucker-Cohen's various web and telephone projects such

as Audiobored

& Audiobored Machine, Phonetic

Faces and Musical/Devices.

0100101110101101.org's VOPOS

is also a clear sign of this reflection on 'convergence' in relation

to the earlier 'purism' with a clear focus on HTML- and pc-based

net art. And it does not have to be about the "disappearance

of the body" or a technologically extended body, as in an artist

such as Stelarc in the

1990s. I think art has moved a bit away from this area, which especially

grew out of the Virtual Reality discourse. Instead, for example

data visualisation, monitoring, access and alternative software

development has become the code words, in the same way as we also

see more works of a more traditional, purely aesthetic character

within net art, with stories not necessarily about the network,

the code, etc. As an example of this see David Clark's a

is for apple.

Images from David Clark's a is for apple

Quite a lot of net art has, more or less, the characteristics

of technology as its content. Is there any reason why net art should

be about networks, information flows and computer code?

Both yes and no. In the early phase of net art - the one often termed

'net.art.' with persons such as Alexei

Shulgin, Jodi, Vuk

Cosic, irational etc.-

focus was on exploring the new media as is typical when a new media

emerges (compare with e.g. photography and video art). The flickering

browser windows and blinking codes (Jodi),

the hacker mentality and the tactical use of media (Critical

Art Ensemble, rtmark, etoys,

Toywar etc.) and the pseudo-avant-garde experiments with for example

Alexei Shulgin's Form

Art meant that the net's processes and building blocks were

put at the forefront, at a time where exactly that kind of realities

were being covered by a sleek, commercial frosting.

Today when encountering code, information flows and the 'technocratic'

use of language on different sites (the tendency still exists in

different forms, see for example Florian

Cramer, mez,

jimpunk) a distinction should

be attempted made between a deconstruction in this original sense,

and a more 'poetic' use of code (see e.g. Graham Harwood's Lungs

and some of the works from Whitney's CODeDOC),

a focusing on the creative dimension of programming itself (as promoted

by John F. Simon Jr.) and

finally that which is merely show off with a technological style.

Images from jodi's wwwwwwwww.jodi.org and

Alexei Shulgin's Form Art.

Images from Graham Harwood's Lungs and

John F. Simon Jr.'s Every Icon.

Apart from a certain fetishist approach to codes visible in some

parts of net art (code for the sake of code), the reason for the

latter stylistic showing off is supposedly that the language and

apparatus of computer technology - in step with its development

through numerous generational changes - appears as historical. Computer

technology has therefore joined the general 1990s' retro- and nostalgia-trip

- the old ZXSpectums and C64s are brought out from their hiding-places.

This is why retro-technical expressions such as 'syntax-error' and

Atari logos emerge on T-shirts, as likewise pixellated symbols are

seen in printed materials and music videos. All because the computer

iconography appears as historical. This kind of meta-stylistic playfulness

does not really have much to do with the technical side of the code,

which is still reserved for the specially selected (most widely

spread within hacker mythology).

The Matrix films are typical of mainstream cultures fascination

with the equilibrists of the computer subculture, the glorification

and the turning into myth of the code aspect itself (cf. Link and

Neo's ability to read 'reality' directly in the stream of code.

In that universe the code equals truth - at the same time as the

film's many special effects are in themselves a deception created

with code).

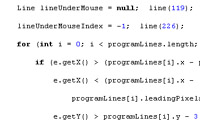

Excerpts of work and code from W. Bradford Paley's

CODeDOC-project: CodeProfiles.

There are thus many different motives and strategies at play when

speaking of this interest in the code. This year Ars

Electronica is choosing 'Code' as their theme and very apropos,

connects computer code with genetic coding. An exhibition such as

Christiane Paul's CODeDOC

at Whitneys Artport was

an attempt at, in a concrete way, to put the program at the foreground

instead of the result of the program, and at finding the auteur-like

grips in the artist's way of programming.

In recent years, certain net artworks have received awards from

art institutions while the creators do not really see themselves

as artists. I am here thinking of for example some of the Ars Electronica

centre's granting of awards. Some of the creators even deny that

the awarded projects are art. Why do you think this occurs so often

precisely among the computer/internet based arts - and what does

in mean for the perception of the works?

Speaking about the granting of awards which have had a social

or political dimension, such as Ars Electronica's award for GNU/Linux

in 1999, they are an expression of a general tendency I think,

rather than something specifically characterising computer/internet

based art forms. With the contextual art, interventionist art and

the relational aesthetic, and what else it has been called, we have

seen a marked interest in art's social function, art's ability to

create alternatives, a better way of inhabiting the world, as Bourriaud

wrote.

If we, on the other hand, look at Ars Electronica giving Joshua

Davis' PRAYSTATION an award two years later, then we are dealing

with something quite different, that is, an interest in the creative

development within for example web design.

The Linux-penguin and an image from Joshua Davis'

Praystation.

The two examples sketch a quick picture of what is going on: i.e.

the widespread perception that the most advanced digital art might

not be created by those calling themselves artists, but by programmers

and product developers who in an open collaborative way create software

alternatives. In regards to what these granting of awards mean for

the reception of the digital art, I think that they are most interesting

and important from the viewpoint of art. I do not think that it

profits GNU/Linux noticeably that they have received a Golden Nica

award at Ars Electronica, neither ideologically, financially, nor

in relation to the productivity of the product. But within the digital

art (and art in general) that kind of decisions can contribute to

moving some borders.

Do you have any tips on current exhibitions, media art festivals

or other places where computer art or Internet art ca be experienced

outside the net?

As we do not have a distinct forum for it here, you have to travel

around quite a lot. Even though net art generally can be experienced

from a computer anywhere, it is interesting to see what environment

people work in, and its also not a disadvantage to have exchanged

a few words with the people behind it.

But apart from festivals, conferences and exhibitions I have gotten

a lot out of studying the subject from some other perspectives.

Last year I had the opportunity to follow the mounting of a large

exhibition, ABCDF,

at Museo de Bellas Artes in Mexico City, where I during several

weeks followed the people (some of them my friends and not least

my wife Isabel) who were down there to program and create interactive

installations for the exhibition. In spite of the fact that we are

talking about the leading interactive media company in Mexico, it

was a bit like being in the engine room of a ship - we were wading

around in cables, burned out chips, soldering irons, laptop computers

and pizza boxes, and worked from 8 in the morning until 2 in the

night.

Images from the exhibition ABCDF in Mexico

City and Tekken Torture Tournament at c-level in Los Angeles.

It was a far cry from the trendy offices in SoHo where a couple

of years earlier, several of the same people sat around with their

smoothies, getting massages, while cashing in $200 per hour on Flash.

Good for them though - the day after they were unemployed. In Los

Angeles, I several times visited a small artist-run place named

c-level, where exhibitions and

lectures are arranged, and where artists can also receive training

in constructing works with digital technology. This place existed

alongside conventions such as SIGGRAPH

and Electronic Entertainment

Expo at the same place. For me, this kind of contrasts are also

a part of the picture of digital art.

By now it seems that every country in Europe has a media art

festival - are there any signs of something on a larger scale happening

on that front in Denmark?

There have been initiatives of a certain size. 'Media art' not only

mixes with visual art but also literature, films and music, as demonstrated

by e.g. Lab, Datanom,

afsnitp.dk, the new interactive

documentary and feature films from Filmværkstedet, and a couple

of years back, Van Gogh's really good CD-ROMs not to be forgotten.

Electrohype in Malmoe is an example of the effort made to establish

something that could be a permanent forum.

Within net art, in connection with Denmark, we have amongst others

www.artnode.org, www.afsnitp.dk

and why not also mention www.kopenhagen.dk? By the way, these are

all admirable precisely because they keep going. It is decisive

that things are both created, and that a discussion can be continued.

But I am not sure that for example the festival form is the right

thing. It is insane to mount interactive installations and then

dismount them three days later. At the same time, I think that it

is problematic to ghettoise the digital art in separate festivals

or exhibitions. It is too important for that, it should reach a

broader audience, and I think that it would also at the same time

become better by being challenged by the 'non-digital' art. The

digital art is important because it often comes close to (and has

a deep insight into) the processes that increasingly control our

culture and society - from graphic effects to digital surveillance

and globalized communication. But, as for example Geert

Lovink has pointed out, the digital art is lacking behind in

other areas, both aesthetically, politically and culture analytically

speaking. Paradoxically at the same time as the digital technology

is culturally gaining influence.

The question of if we will get - or should have - a special forum

for media art, is connected to the problematics characteristic of

photography: should photo art be shown separately at exhibitions

and museums, or should it be mixed with the other visual art? It

is a difficult question. Something might be better understood within

a more narrow genre, tradition or media discourse, while something

else might do far better without this specific frame of understanding.

I would therefore rather answer your question with a new question:

In what frame would we prefer to see the digital art?

|

|

|