|

[May 13th 2005]

From Untitled 5. Image courtesy of Camille Utterback.

An Experience with Your Body in Space!

- Interview with Camille Utterback

Camille Utterback, a digital artist from New York, is famous for her interactive installations and her use of advanced video tracking technology. Emil Bach Soerensen met her for a talk about Untitled 5, a generative artwork where the physical presence of the audience has agency in a real time painting process. Utterback received one of the transmediale.05 awards for this piece. The talk about Utterback's video tracked universe turned out as an alternative route involving visions about the artwork as an opening, intuition in the process of coding and a strong claim for embodiment in the digital age.

You just won an award for your piece Untitled 5 here at Transmediale. Congratulations! Maybe you should describe the work with your own words, now that we are standing in front of it.

Ok! Well, I sometimes thought of it as a living painting, but this isn't quite right because it has a momentum that is more like a kinetic sculpture. It's a system that has rules about how things can move in it, and then these rules are combined to make an overall composition. We can watch these people that are walking through the video tracked area! The first thing that happens when you enter the video tracked area is that you see grey marks around your body. Then your trajectory is filled with a colored line. As soon as you have left your position, other little marks appear along that line. This is marking different kinds of time. The little grey lines are there immediately but they don't leave any trace, they are just the immediate presence.

From the exhibition of Untitled 5 at transmediale.05 in Berlin.

The presence of the body in space.

Yes exactly, and then the path is the more boiled down idea of how you moved. Basically, it's your centre point that I'm tracking. This is showing where you have moved over time. It's also paying attention to the speed of your movement

since this will determine the size of the marks on the trajectory line, so it creates variation this way as well. Let's look at the piece again... What happens now is that he has moved across the line that the other person put, and all these greenish marks that were along the first person's path got pushed out of the way, and then they draw as they return to their original location. It's like second or third order movement because the marks don't draw when they are pushed out of the way; they draw when they are going back. In this work I am conceptually interested in thinking about movement or connections between people. I'm making an abstract visualization about how people intersected in time.

Layering traces of different persons - is that adding a social dimension to your work? At the press conference you said that Untitled 5 is not very socially or politically engaged. How social is your work?

I think it is socially engaged, because obviously people have some dynamics with each other in front of Untitled 5. You can have more than one person negotiating how to move in the video tracked area. If they are friends or not friends they might interact differently. Strangers might start moving in different ways when they see each other's movements here, so it's definitely a social piece. And - I don't know if this is very social - but it's definitely a process of discovering and exploring yourself in the piece.

You also said to the press that your piece creates some kind of an opening. Can you try to explain that a bit more?

Ah! It is hard to talk about that without sounding weird or spiritual but I do feel that if people have an experience in this piece where they are open to questioning things, then...

I think the process goes like: 'Oh this thing is reacting to me!' And then you ask: 'Well, how is it reacting to me?' There is nothing written in here, so the only way to discover that is to try things out, and you start thinking: 'What happens if I try this? What happens if I try that?' I think this questioning mode puts you in a state where you are present, aware and very open. And I also believe that you are most creative, when you are in that kind of mode. As an artist I have to put myself in that mindset to make the work.

I guess it's about allowing yourself to be in a space where you don't really know what you are doing and where you don't really know what is going on, but where you are engaged. I like to think that helping people to have that kind of experience might change how they approach things in a very subconscious way after they leave this space. I don't know if it is possible to transfer the experience directly, but I feel strongly that it is important to have these kinds of open spaces in our social reality.

This sounds very much like an artist in general, and it goes for many works of art. But in terms of being a computer artist I tend to think of programming as something rational. And you talk about being intuitive and loosing yourself. How do these two sides correspond? Rational programming and being intuitive at the same time.

Well, how I work drives some of my friends crazy! I think there are different ways for working with technology. It is complicated and you do have to code and sit down and work out these problems, which is a little less direct than using a paintbrush. The more you do it, the more it becomes like using a paintbrush, but it still doesn't feel quite so viscerally connected to me.

I think some artists work in a way where they have planned everything, and have a very specific vision or goal for what they are trying to do. Then you can almost hire someone, to do the technological part of the work. But I am doing my own programming and I have to do that because I didn't have a specific vision about how this piece should look like when I started. I began playing and developed these systems. In the same way as you would compose a painting I layered it together in the end. But it was always trial and error. In that process you get to a lot of dead ends where you feel: 'Oh it's really ugly today'. You have to not freak out when you get to these dead ends and stay open to your ideas.

From Untitled 5. Click to enlarge. Images courtesy of Camille Utterback.

Maybe you can you tell a bit about the technical aspects of your work? For someone who is not into programming already!

It is pretty simple. A video camera is an excellent input device, because it gives so many points of information. A computer mouse is one point in action-wise space. But if you think about all the pixels in a camera image as information, it really contains a lot of information about the space! Now, the tricky part is to decipher that image to decide where a person is. I do that by taking a still image of the space with nobody in it when the program starts, and then I'm working at every frame coming into the camera and comparing it to the picture of the empty space to tell if there is somebody there. The difference between the images is the person.

What is a little harder is to figure out from frame to frame if it's the same person. It is amazing what we do automatically in our brains! Like the idea that just because someone is here, and now here, it's the same person. The only way that I can do that is to compare if the image of the person is overlapping in the different frames. When they overlap by a certain amount I'm going to assume that it's the same person.

And it might not be.

Right! When it's not, it's because we touched shoulders and then came back apart. Then it's impossible for me to tell exactly what happened. And there is also another problem, which is philosophical but interesting. How do I decide if a person is standing still? What is the real definition of stillness? In coding you are making assumptions and simplifying things to a certain degree. My rule about stillness is that a shape is overlapping between frames in time and the centre of it is not varying by more than say 20 pixels. But that is arbitrary, I could say 5 pixels, and then you would have to be so still that nobody could do it.

We are obviously standing in front of some kind of an interface here, but not a normal Human Computer Interface. What is your opinion about interfaces if we talk about computer culture in general? In which way do you think the design of HCI is developing and how can your work inspire for the development of new designs or new ways of perceiving HCI?

I don't know if video tracking will become a practical interface for doing the work tasks we have to do on our computers. But I hope that if people see this piece then afterwards they might be a little pickier about the interfaces that are surrounding us more and more. Everything has its own interface. You are an interface and the bank machine is an interface. But a lot of the interfaces that we are surrounded by are designed terribly, so they make us feel stupid and frustrated.

It is like the classical problem of the door handle. Donald Norman is a writer and designer and he talks about how you see everywhere these doors that have the sign 'PUSH' or 'PULL' on them, which is absurd. What it means is that the handle looks exactly the same on both sides, so you have no clue whether you are supposed to push or pull. If the door handle is designed well, you don't even think you just push or pull because it is so obvious from how the handle is that this is what you should do. Even though there are these signs people are always doing the wrong thing! I think it's a very good lesson about design that people react in an amazing and intuitive way to the things they meet. If you get frustrated by a design, it's not you but the designer who is dumb. With HCI it's the same problem - it's a little more complicated than with the door but it is the same issue.

From the exhibition of Untitled 5 at transmediale.05 in Berlin.

What you are saying is that HCI has to work in a more intuitive way?

I don't know if it needs to be more intuitive, but it needs to be well designed, so that your instincts about how it should work make sense. Here, with the video tracking, I give you a clue, which should make you understand something about the system. Part of the problem is that with interfaces you don't necessarily have a real world metaphor or experience with it. So since it is all virtual you have to be even clearer about the clues that you give people. This is why the whole desktop metaphor caught on so well at first, because it gave people a way to think about these paths. To delete something is abstract, but everybody knows what it means to throw something in the garbage can, so that icon helped people to understand the activity.

Now the desktop metaphor is starting not to be functional. There are tons of situations where this metaphor becomes unwieldy. We have so many files now that there are better ways to show information than by using folder structures. So probably interfaces based on desktop metaphors will change into other ways of showing information. Anyway, I hope that people who have an experience with Untitled 5 can maybe also make the leap to say: 'Why do these other experiences with HCI have to be so frustrating?'

So it is about giving people good experiences with computers?

Yeah! I think most people who see this piece don't think that they are having an experience with a computer or a computational system. I think they are having an experience with their body in the space. Machines and the technology disappear when it becomes part of our life. We don't think of turning on the light as having an interaction with technology, but of course it is. You are having a very complicated interaction with the whole system of electricity; including wires, switching machines etc. But because the interaction is not causing you problems, and you understand the metaphor for switching on the light, it disappears from our thinking about it as technology because it just works!

Does it matter to you where your works are exhibited? I mean, we are now at a festival for new media art, but when the technology behind the pieces disappears the works could as well be exhibited at any art festival?

Yes, definitely. This topic was part of what we were talking about in the panel discussions. Is it bad in a way to show this work in the context of new media, because does that mean that it's not just contemporary art? I think the reality is that it is still hard for a lot of traditional art spaces to show a piece like this. They are not sure how to talk about it, and they are not sure how to sell it. Yet! And it does involve some amount of cables and cameras etc.

It is important for me to be in a festival like this. Also, because when you are with other people dealing with similar issues, you get a lot of good feedback. I had a gallery show in New York recently, and I even got a review in Art in America, which is a big art publication, but it was not helpful to me at all, because all the review did was to describe very basically: 'Here is the piece and when you move it reacts to you'. It didn't say anything about the aesthetic issues and all the things that we have been talking about! People at this festival are thinking about these issues, so I get a lot of good feedback, which I wouldn't get in other contexts. Hopefully that will change over time.

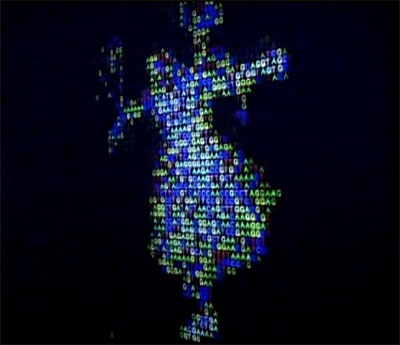

From Drawing From Life at The American Museum of Natural History,

'Genomic Revolution' exhibit, New York, 2001. Image courtesy of Camille Utterback.

We already talked about crossing the border to design. You are both an artist, you teach at Parsons School of Design and you have your own firm, Creative Nerve, which, in addition to your works, is trying to see how your artistic ambitions can be transformed into design and communicative strategies. I know that you have done pieces for Children's Museum in Pittsburg and for The American Museum of Natural History. How do you see that artistic ambitions, and now we are talking about digital art, can be transformed into new designs and new ways of communication?

Occasionally I have done pieces where there is a specific goal of communicating something through the work. For The American Museum of Natural History, the show that I was in was about the human genome, and it was a very didactic exhibit. They wanted an experience for people that made them a little more self-reflective. My piece was exhibited in the last room, where you saw yourself on a screen, but turned into letters. We were hoping that this experience would raise some awareness in people about the question: 'What is a representation of yourself?'. DNA describes a certain way of looking at yourself, but you are so much more than that, which was what they were trying to show in the exhibit.

My work is trying to bring the bodily experience back into technology. You always use your body. You use your body when you are typing on the keyboard and when you are moving the mouse around. But these activities are only activating a very limited amount of our body and a limited amount of your knowledge about the world. It could be interesting to take some of the other things we do really well or know well into account. Human beings have evolved over millions of years and we always had a body, which we sometimes tend to forget! Using the body is actually how we first learn about the world.

So, this is important to remember as things get more and more digital and immaterial, you would say!

Yes! A lot of my works deal with the sense of embodiment. I have a piece called Liquid Time which is playing with the idea that in English you say: 'Where do you stand on this issue? What is your point of view?' All these things imply that you have a body somewhere in the world, and that we use the body to refer to consciousness or intellect. So I'm really interested in the idea that we have a body and how integral that is to who we are and how we function and that it sometimes gets lost in all our media.

More:

http://www.camilleutterback.com

http://www.creativenerve.com

|

|

|