|

[January 22nd 2007]

Douglas Gordon: 24 Hour Psycho, 1993. Photo: courtesy of the artist and Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Smithsonian Institution, Washington. Photographer: Christopher Smith. Film stills from Psycho, 1960. Director: Alfred Hitchcock.

Learning Embodiment from Film and Video Art

An Interview with the Curator Joachim Jäger from Hamburger Bahnhof

Contemporary digital art and design dealing with augmented reality and embodied interfaces can learn a lot from film and video art. The large retrospective exhibition Beyond Cinema: The Art of Projection at Hamburger Bahnhof (Museum for Contemporary Art in Berlin) demonstrates that film and video art adds critical perspectives as well as vital nuances to interaction and exchange between embodied human life and technologically based media. Emil Bach Soerensen spoke with Joachim Jäger, curator at Hamburger Bahnhof, about the exhibition and about the role of moving images today. Introduction also by Emil Bach Soerensen.

Introduction

In late modern culture we have witnessed how moving images have migrated from movie theatres into private as well as public spaces distributed by media such as television, computers, mobile devices, signs, commercials etc. The moving images are often remediated as responsive media reflecting the interaction of the user. As technology and the consumption of images become more advanced, the interaction increasingly involves different aspects of the user's embodied presence. At Hamburger Bahnhof visitors can experience how the connection between moving images and embodied human life has been an essential concern for film and video art from the early 1960s to present day.

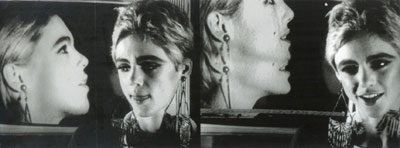

Dan Graham: Body Press, 1970-1972. Photo: Dan Graham, courtesy of the artist and Marian Goodman Gallery, New York and Paris.

Physical expressions have often been a subject for video art, which can be seen in works such as Andy Warhol's Outer and Inner Space (1965), or Bruce Nauman's Raw Material with Continuous Shift-MMM (1991). Cameras have been intimately connected to, even attached to the body by Dan Graham's Body Press (1970-1972) and Valie Export's Adjungierte Dislokationen (1973) in order to challenge the logic of the stable lens. Finally, physical movement and embodied presence of the audience in the exhibition space have often been involved directly in art experiences mediated by technology: works such as Peter Campus' Prototype for Interface (1972), or Doug Aitken's Eraser (1998).

The current trends for physical computing, augmented reality, pervasive computing, embodied interfaces etc. draw heavily on experiences from other media forms, and much can be learned about embodiment from the film and video art exhibited at Hamburger Bahnhof. If you are in Berlin for the digital media festival Transmediale.07, you should definitely consider visiting Beyond Cinema: The Art of Projection as well.

The exhibition runs until February 25th, 2007.

For more information see: www.hamburgerbahnhof.de

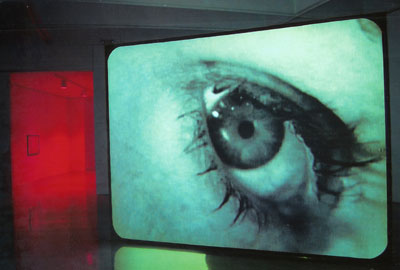

Andy Warhol: Inner and Outer Space, 1965. Photo: courtesy of the artist and The Andy Warhol Museum, Pittsburg.

We are all familiar with the scene in the traditional film theatre: we are sitting relaxed - but also physically fixated - in deep and soft chairs; the light is switched off, and for two hours we are compelled by the moving images projected on the screen in front of us. In your catalogue text you explain how film and video art from the 1960s until present day, offers alternatives to the physically 'passive' consumption of images in the movie theatre. How has the aesthetic examination of space and the physical expressivity of the human body in video art transformed the notion and the role of moving images?

The notion and the role of the moving image, from the early movie-days until the present time, have changed caused by a wide range of reasons. Not only artistic ideas and aesthetics have changed the modes of films or videos, but also technical inventions, philosophical ideas and the culture of everyday life. Our time today is faster than it was 100 years ago - although it was subjectively experienced as very fast already in the 'roaring twenties', but computer technology with its effect on telecommunication, and also speed transportation, has changed our perception completely. Today, we are able to process many visual signals at the same time. This ability was connected to the notion of 'modernity' for example by Charles and Ray Eames in 1964 with their famous multi-projections for the Moskau world fair. With computer window systems, the ability to read and work on several levels and 'windows' of information at the same time became common for everybody.

Pipilotti Rist: Ever is Over All, 1997. Photo: courtesy of the artist and Hauser & Wirth, Zürich London. Photographer: Alexander Troehler, Installation view at Kunsthalle Zürich, Zürich/CH.

Artists working with projections have transferred such experiences into the open field of space. The contexts the artists explore, however, are various, whether you look at a work of Diana Thater, who always de-constructs the illusion of space in her projected videos, or you focus on Pipilotti Rist, who combines images, music, and space to an extent in which you can no longer separate these elements in her installations. These spaces of fusion have been inspired by the lounge architecture of clubs, but her popular installations have also inspired TV shows, advertisements, and urban living. The transformation of moving images never happens on a single route, but results from a constant mix of changes and interrelations.

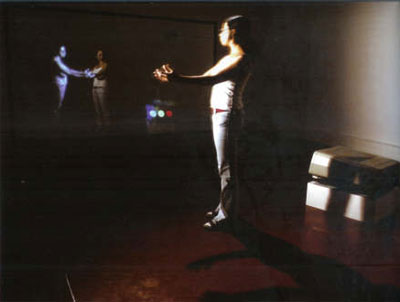

Peter Campus: Prototype for Interface, 1972. Photo: courtesy of the artist and Leslie Tonkonow Artworks + Projects, New York.

Experiencing interactive digital art installations, I often feel that the open aesthetic of these works investigate a tension between two layers/levels: one represents a direct reflection of my physical presence in the exhibition space, and the other, which perhaps is more critical, raises new aesthetic concepts and fundamentally challenges my perception. Is this relationship between immediate physical presence and aesthetic critique reflected in the film and video art you exhibit?

I would not separate the 'personal' experience of film and video in space from a view on a somehow 'general' aesthetic of the work. Both come together. The montage of the film, the images chosen, the theme of the work, the way the film is projected, the medium - whether film or video, the architecture, the sound, the openness of the space – all these aspects merge into one large aesthetic. To show these dimensions of film in time and space on a professional museum level was in fact one reason to make this show.

Doug Aitken: Eraser, 1998. Photo: courtesy of the artist and 303 Gallery, New York.

The title Beyond Cinema stands for a wide variety of modes of perception. Looking at an installation by Doug Aitken, for instance, means that you cannot overlook the total work. You have to move to see all elements of the work - missing some images while you see others. Viewing a projected multi-screen film work is therefore closer related to the experience of theatre and performance. There is no singular view, there are many, depending on your position, your relation to time and space. Of course, you could describe the filmed tour of Doug Aitken through the island of 'Montserrat' as it is presented in the seven films of the installation Eraser, but then you would only experience one aspect of this work. The narration would not reflect the full connotations of the installation. In order to grasp the full experience, you have to take into account where you stand inside the installation, and at what you are looking at in this or that moment. To sum up, I would say that projected art is perceived in highly subjective ways - and by that reflects our contemporary and very individualized existence.

Diana Thater: The best space is the deep space, 1998. Courtesy of the MAK Center for Art and Architecture, Los Angeles, California, USA. Photographer: Fredrik Nilsen.

How do you think an art exhibition like this can inspire people outside the traditional arts sphere to think more critically and creatively about the relationships between technology, media and the complex life of human beings?

Contemporary life is very much affected by media influences: what we wear or eat, how we dress, what kind of books we read, or what we like to see in the movies. All this is pre-coined through media coverage in papers, magazines, ads and television. Especially images - large-scale and multi-reproduced images - play a central role in this media stream of everyday-life. In great cities, like New York, London, Tokyo and partly also in Berlin, we are surrounded, not only by still images, but also by ever moving images: moving images displayed on flat screens, on info screens, or large-scale-projections on buildings or banners. Often we experience our own movement through the city by reacting on those images, defining our position, navigating through them by looking at them, or demonstratively overlooking them.

An exhibition like Beyond Cinema, which is so much based on the interaction of space and images, is a reaction on that experience. Or better: the artists who created film and video installations decided to project into space, because they realized how much in our life we relate to projected images. So they created works of art in which the parameters of space and projection, image and sound, as well as scale and distance play a central role. Experiencing these dimensions in an exhibition, in the abstract and somehow ideal sphere of the arts, will hopefully bring inspiring thoughts and reflections about our everyday-life, and about the constant use of moving images in our urban environments.

Valie Export: Adjungierte Dislokationen, 1973. © VALIE EXPORT, VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2006. Photo: Sammlung Generali Foundation, Wien. Photographer: Werner Kaligofsky.

|

|

|